Andrew Sullivan's Conservatism of Doubt

How the legendary blogger can show us how to be conservative without being ideological

What does it mean to be conservative? This is the question which befuddles anybody who identifies his politics with the label, including myself. Does it mean being a supporter or a detractor of Donald Trump? Does it mean upholding traditional American institutions or placing them against popular will? Should a conservative advocate for free trade or apply protectionist measures to secure American jobs? Should a conservative foreign policy be more interventionist or isolationist? Tucker Carlson, the most (in)famous Right-wing figure in American, shares his economic views with Elizabeth Warren, a Senator from the Left wing of the Democratic Party. And while he was still on Fox’s payroll, one of Carlson’s most frequent guests is Glenn Greenwald, the Chomskyite, left-wing journalist who broke the story of Edward Snowden and the NSA. As recently as 2022, a new online journal named Compact entered the Internet. Dubbed “a Radical American Journal”, it was founded by two traditionalist conservatives, Matthew Schmitz and Sohrab Ahmari, and one Marxist populist, Edwin Aponte.

It was George F. Will, modern conservatism’s most influential columnist, who says that the American conservative’s main purpose is to preserve the Founding. But as Israeli philosopher Yoram Hazony recently shows, even that has become an ambiguous undertaking. According to his latest book Conservatism: A Rediscovery, Hazony traces two conflicting ideologies that underlies the Founding Generation. The Hamiltonians, he explains, are nationalist, pro-England, and in favor of a strong central government. By contrast, the Jeffersonians are heirs to a universalist Enlightenment liberalism, in favor of the French Revolution, and in favor of a limited federal government. It was this “rediscovery” that led Hazony to spearhead a movement called National Conservatism, wherein the nation-state is emphasized over the individual, traditional values over classical liberal rights, and a strong government to enforce these values rather than a limited liability state. After the four years of political and social turmoil that Donald Trump’s presidency has wrought, the national conservatives’ profound skepticism of classical liberalism is sounding more convincing than ever, all the while the defenders of liberalism sound tepid and out-of-touch.

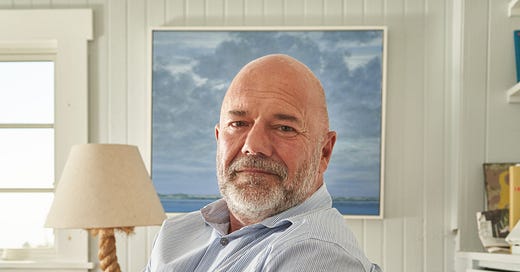

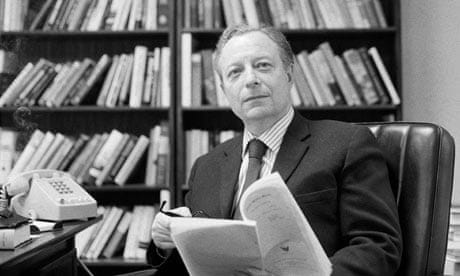

Perhaps the most prominent conservative commentator who has both feet in the liberal and the nationalist strands of conservatism is Andrew Sullivan. Drawing from his experience as an immigrant to America from Britain, he is well-versed in the both conceptions of conservatism - one as defined by the Americans, and the other by the British. However, his greatest philosophical influence comes from Britain - the great political theorist and professor Michael Oakeshott (1901 - 1990).

For Oakeshott, as with other notable British conservatives like Sir Roger Scruton and John Gray, conservatism is a disposition, not an ideology. “To be conservative,” Oakeshott writes in his wonderful essay On Being Conservative. “is to be disposed to think and behave in certain manners; it is to prefer certain kinds of conduct and certain conditions of human circumstances to others; it is to be disposed to make certain kinds of choices. And my design here is to construe this disposition as it appears in contemporary character, rather than to transpose it into the idiom of general principles.” Because of that, it has no fixed ideological positions, and does not aim at a final end of human progress (unlike communism or classical liberalism) or progress merely for its own sake (unlike the American Progressive movement of the early 20th century and their progeny today). Seconding this line of thought, Roger Scruton said: “Conservatism is more an instinct than an idea. But it’s the instinct that I think we all ultimately share, at least if we are happy in this world. It’s the instinct to hold on to what we love, to protect it from degradation and violence and to build our lives around it.” John Gray, formerly a strong supporter of Margaret Thatcher, nevertheless exhibits his conservative disposition as he laments the overwhelming influence of neo-liberal market fundamentalism following the end of the Cold War:

A political outlook, that in Burke, Disraeli and Salisbury was sceptical of the project of the Enlightenment and suspicious of the promise of progress, has mortgaged its future on a wager on indefinite economic growth and unfettered market forces. Such a bet — Hayek’s wager, as it might be called — hardly exhibits the political prudence once revered as a conservative virtue.

This lack of a concrete political program is perhaps what separates British conservatives from their peers in America. This opposition is best articulated in an essay by Irving Kristol in response to Oakeshott, titled The Right Stuff. While “admiring the essay immensely”, he did not like it. Kristol’s objections to Oakeshottian conservatism are twofold. First, he disliked the secular nature of it: “Oakeshott’s ideal conservative society is a society without religion, since all religions bind us as securely to past and future as to the present. The conservative disposition is real enough, but without the religious dimension, it is thin gruel.” Second, and more important, Kristol did not believe that Oakeshott’s non-ideological conservatism would fit the American spirit. American conservatism, Kristol believes, is a movement, and thus is uneasy with the stasis valued by her British counterpart.

Matthew Continetti’s illuminating history of the American Right traces this movement back to William F. Buckley’s fusion of the libertarian thought of Friedrich Hayek and the traditionalist views of Russell Kirk, against what they deemed to be the Progressive political establishment of post-WWII America. Because of this, while the British conservatives perceive of themselves as the establishment, American conservatives are anti-establishment from the outset, even to the point of revolutionary. A notable example of the latter is Patrick Deneen, who sees himself as a “common good” conservative. In his new book, provocatively titled Regime Change, he suggests a radical overhaul of the classical liberal status quo: “Merely limiting the power elite is insufficient. Instead, the creation of a new elite is essential… Only such a new elite, in turn, can begin to use political power to alter, transform, or uproot an otherwise hostile anti-culture that is today dominated by the progressives on both the right and the left within modern liberalism.” Such revolutionary rhetoric is also employed by Michael Anton in his influential essay The Flight 93 Election, which provided the intellectual basis for Donald Trump’s hostile takeover of the American presidency. On the other side of the Atlantic, the neo-liberal consensus which John Gray criticizes prompted an anti-establishment revolt of its own, in the form of Britain’s exit from the European Union (or Brexit) - rendering the populist firebrand Nigel Farage an unlikely hero among British conservatives. This tempestuous pact between populism and conservatism, not without historical precedent in both the United States and United Kingdom, is precisely described in Michael Brendan Dougherty’s recent piece on National Review:

The English philosopher Roger Scruton located populism’s danger precisely in its prophetical character. Populist leaders ride majorities to vanquish their opponents, not compromise, conciliate, and govern with them like true democrats. So it is true that there is a tension between populism and conservatism. The populist mode can be an obstreperous, even deranging ally.

What does Kristol think of populism? As Continetti has pointed out, he has gone back and forth on the subject: “In the 1970s he fretted over populism’s tendency to devolve into lawless revolt, conspiracy theory, and scapegoating of vulnerable minorities. By the mid-1980s, however, he saw the activism of the populist New Right as ‘an effort to bring our governing elites to their senses.’” Perhaps the task of every conservative today is to recognize the abject failure of our governing elites to maintain good, responsible government, all the while being wary of populism’s passionate lawlessness. In this manner, Andrew Sullivan is a rare figure who manages to harmonize both viewpoints.

I have treated Sullivan’s conservative defence of gay marriage in a different essay. So for this one, I would like to introduce readers to his efforts to reconcile both the British conservatism of Oakeshott and the American (neo)conservatism of Kristol, using three illustrative examples:

I.

Twenty years have passed since the first set of U.S. military boots landed in Iraq, and however one may think of the Second Iraq War (the first, being dubbed The Gulf War, occurred in 1990-91), it can be reasonably concluded that the governing elites have failed to hold themselves accountable for the operation’s glaring shortcomings. Talks about the “neoconservative” elites and the “military-industrial complex” coming from Democrats such as Tulsi Gabbard and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have found an easy audience in both the Sanders-supporting Left and the Trump-supporting Right. Although this betrays a gross mischaracterization of neoconservatism’s political philosophy, it is reasonable to conclude that American foreign policy after the September 11th attacks, largely advocated by neocons such as David Frum, William Kristol (Irving’s son) and Max Boot, has neither been beneficial to the American national interest, nor has it improved America’s standing in the international stage. This is the same conclusion reached by Andrew Sullivan as he watches the catastrophic failure of the Bush administration in Iraq, at the chagrin of his friends in the neoconservative circles. Initially supportive of the war effort, Sullivan came to regret his previous stance, attributing it to the trauma and anger caused by the terrorist attack on American soil:

One of my own errors before the war was a function of being steeped in Washington policy debates – and neoconservative arguments – for years. I had been so conditioned to suspect Iraq after 9/11 that my skepticism deserted me. I mentioned Saddam on September 12. The result was that the prelude to the Iraq war was far too easily framed by the information and biases of the Beltway elite, the Pentagon establishment, and the neocon brain-trust. Worse, we were unspeakably condescending to those on the outside who were right. We trusted far too much, and people much further away from the levers of power saw more clearly than we did.

This blog entry was written in July 27th, 2007. Compare this to a piece written four years ago, on July 18th, 2003:

The burden of proof must be on those who counsel inaction rather than on those who urge an offensive, proactive battle. Does it matter one iota if we find merely an apparatus and extensive program for building WMDs in Iraq rather than actual weapons? Or rather: given the uncertain nature of even the best intelligence, should we castigate our leaders for overreacting to a threat or minimizing it? Since 9/11, my answer is pretty categorical. Blair and Bush passed the test. They still do.

Hindsight being 20/20, it should be clear by now that the WMDs were only a pretext to the Iraq invasion. The real objective, as stated clearly by the neo-con brain trust, is to depose a vicious dictator and replace him with a stable representative government. Twenty years on, the dictator has fallen, but stability is nowhere to be found. But the real damage of Bush’s misguided foreign policy is visited upon American society. As the government elites continue to pledge their support for the war, a left-right coalition begins to form in opposition to it.

II.

What unites the Chomskyite journalist Glenn Greenwald, the libertarian Godfather Ron Paul, and the paleoconservative Pat Buchanan, is their fervent opposition to the war effort and their acute perception of the American people’s discontent. In addition to the Recession that struck American and the world in 2008 - 09, public opinion has shifted away from “left vs. right” and become “the elites vs. the masses”. The Occupy Wall Street movement finds its right-wing counterpart in the Tea Party.

Out of Occupy emerged Bernie Sanders, and out of the Tea Party appeared Donald Trump. In 2016, caught in between the two firebrands, Hillary Clinton and her supporters doubles down in their contempt for the American mass. No one saw this more clearly than Andrew Sullivan. Channeling his inner Irving Kristol, he warns of the coming populist tidal wave while chastising the political establishment for their complacency:

It seems shocking to argue that we need elites in this democratic age — especially with vast inequalities of wealth and elite failures all around us. But we need them precisely to protect this precious democracy from its own destabilizing excesses.

And so those Democrats who are gleefully predicting a Clinton landslide in November need to both check their complacency and understand that the Trump question really isn’t a cause for partisan Schadenfreude anymore. It’s much more dangerous than that. Those still backing the demagogue of the left, Bernie Sanders, might want to reflect that their critique of Clinton’s experience and expertise — and their facile conflation of that with corruption — is only playing into Trump’s hands.

Had the United States been a stable liberal democracy in 2016, Donald Trump’s campaign would not have lasted longer than his escalator descent. However one thinks about his presidency, Trump has both exposed and exploited the legitimation crisis facing Western liberal democracies. It is not surprising that the most vocal opponents of Trump on the right were the most vocal supporters of the War in Iraq - David Frum, William Kristol, Max Boot, among others. Sullivan’s essay, published in New York Magazine, was titled “Democracies End When They Are Too Democratic”. But democracies can also end when the majority ceases to believe that democracy is a workable political model. In the case of Trump, a hard populist tyranny was considered a viable alternative to the soft tyranny of public opinion. Neoliberalism, with its promises of including a vast number of the world population into a global free trade system, brought about the erosion of national borders and displacement of unskilled domestic workers. Neoconservatism, with its promise of making the world safe for democracy, failed to bring democracy and stability to the Middle East while neglecting the erosion of democracy at home. This has prompted many self-proclaimed conservatives to adopt extremist language, from Michael Anton (The Flight 93 Election) to Patrick Deneen (Regime Change).

As liberalism becomes trapped in a pincer movement, the only genuine conservative position is to fight a two-front battle against the forces of illiberalism. Andrew Sullivan has enlisted himself in this battle, and he encourages true conservatives and liberals to set aside their differences and join what the political scientist Yascha Mounk deems the Good Fight against authoritarian populism.

III.

The War on Iraq, waged by America against a secular Middle Eastern dictator who oppresses his Muslim population, somehow triggered a heated debate on the compatibility of Islam with Western society. After the September 11th attacks, a plethora of books are published on the topic, such as Bernard Lewis’s What Went Wrong? The Clash Between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East, Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now and Islam and the Future of Tolerance, a transcript of a dialogue by Sam Harris and Maajid Nawaz. At the same time, another batch of bestselling titles proclaim the rise of New Atheism, with the purpose of delegitimizing all religious claims - The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything by Christopher Hitchens, and The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason by the aforementioned Sam Harris. Retrospectively, the 2000s were not a good decade for organized religion. Aside from the looming terror of Islamic extremism, America under President Bush also faced Evangelical fundamentalism at home. The Catholic Church under Pope Benedict XVI labored to reckon with the appalling child sexual abuse/cover-up scandal. And in Israel, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount/Al-Aqsa Mosque, a site considered holy to both Jews and Muslims, shattered the nascent Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Some blamed the needless violence on the religion of Islam, some blamed the existence of religion itself.

Andrew Sullivan, a gay Catholic, personally endured much injustice done to him by his Church. But he cautions against the misinterpretation of the classical liberal concept “freedom of religion” as “freedom from religion”. In a 2007 email exchange with Sam Harris, Sullivan defended religiosity against the notable New Atheist as such:

I believe that God is truth and truth is, by definition, reasonable. Science cannot disprove true faith; because true faith rests on the truth; and science cannot be in ultimate conflict with the truth. So I am perfectly happy to believe in evolution, for example, as the most powerful theory yet devised explaining human history and pre-history. I have no fear of what science will tell us about the universe — since God is definitionally the Creator of such a universe; and the meaning of the universe cannot be in conflict with its Creator. I do not, in other words, see reason as somehow in conflict with faith — since both are reconciled by a Truth that may yet be beyond our understanding.

This line of reasoning is much inspired by the great Medieval theologian St. Thomas Aquinas. However, it raises doubt in irreligious folks like Harris, who believes that religion is unreason:

How does one “integrate doubt” into one’s faith? By acknowledging just how dubious many of the claims of scripture are, and thereafter reading it selectively, bowdlerizing it if need be, and allowing its assertions about reality to be continually trumped by fresh insights—scientific (“You mean the world isn’t 6000 years old? Yikes…”), mathematical (“pi doesn’t actually equal 3? All right, so what?”), and moral (“You mean, I shouldn’t beat my slaves? I can’t even keep slaves? Hmm…”). Religious moderation is the result of not taking scripture all that seriously. So why not take these books less seriously still? Why not admit that they are just books, written by fallible human beings like ourselves? They were not, as your friend the pope would have it, “written wholly and entirely, with all their parts, at the dictation of the Holy Ghost.”

Harris’s atheism, unfortunately, suffers from the same biblical literalism that gave birth to Young Earth Creationism, the proposal of “Intelligent Design” as an alternative to Darwin’s theory of evolution, the Westboro Baptist Church, and many a whacky millenarian cults out there. Those who take the Bible seriously do not take it literally. Bishop Robert Barron once said that the Bible should not be considered as one book, but a library filled with books of different genres. Thus, the question of “Do you take the Bible literally?” is as serious as “Do you go into a library and take every book literally?” And therefore, Sam Harris may be as fundamentalist in his atheism as the Evangelicals and Muslims he criticizes in The End of Faith. Here’s Andrew Sullivan again:

The essential claim of the fundamentalist is that he knows the truth…For the fundamentalist, there is not a category of things called facts and a separate category called values. The values of the fundamentalist are facts. God has revealed them in a book that is inerrant, whether that book is the Bible or the Koran; or he has entrusted them to a hierarchy whose interpretation of scripture and tradition and history and nature is authoritative and even, in some cases, literally infallible.

These words, included in his 2006 book The Conservative Soul: Fundamentalism, Freedom, and the Future of the Right. Upon its publication, Sullivan was essentially blacklisted by the conservative establishment of the time, making him an example of a modern-day Galileo. George W. Bush may be a decent man, but he presided over a party of fundamentalists, from the neocons who are dead set on the legitimacy of the Iraq cause to the Moral Majority who are desperate to prove (Evangelical) Christianity superior to Islam and secularism.

Irving Kristol and Michael Oakeshott may disagree on many things, but they both believe that conservatism, whether it is American or British, is a persuasion and not an ideology. This allows both of them to be free and pragmatic thinkers, as they are not wedded to any ideology, all the while being constantly vigilant of the passions of both the rulers and the ruled. Andrew Sullivan embodies both of these great minds in his writings and commentary, proving that there is always room for doubt in conservatism.