'From Time Immemorial', 40 Years Later

Revisiting a Controversial book on the Israel-Palestine conflict

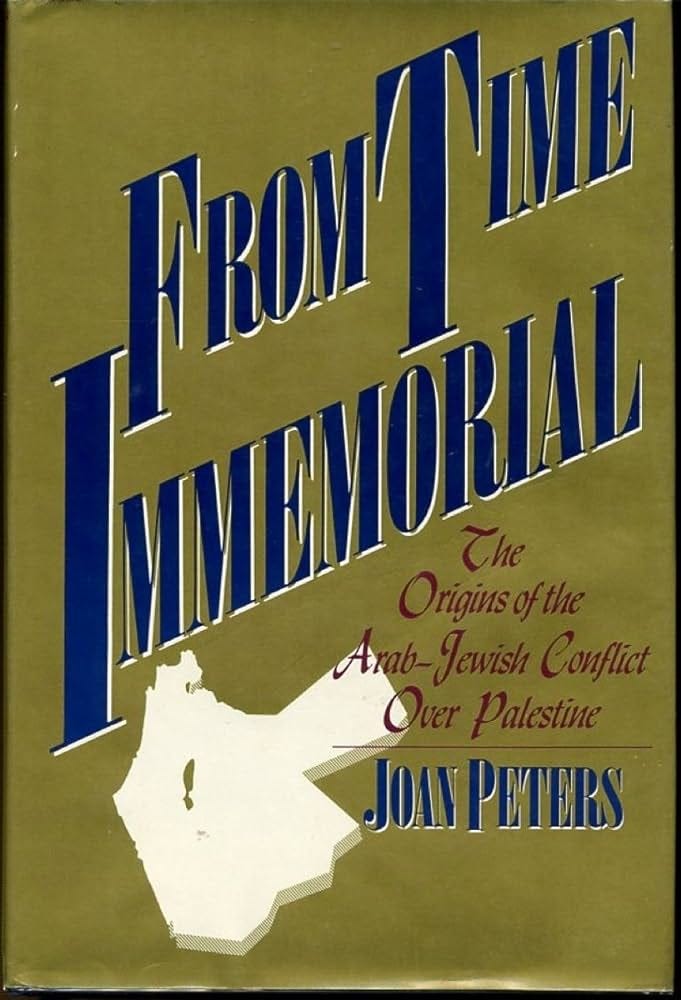

This entry is a continuation of an unofficial series of essays focusing on controversial books: the first essay was about The Bell Curve, and the second about The End of Racism. With the latest round of conflict between Israel and the Palestinians entering its sixth month, I would like to revisit a book whose reception represents the intensity and bitterness that this prolonged conflict has wrought. That book is From Time Immemorial: The Origins of the Arab-Jewish Conflict over Palestine, published in 1984 and authored by Joan Peters.

Never before has a book received so much praise, yet so much scorn. From Time Immemorial earned praises from the likes of Elie Wiesel, Saul Bellow and Barbara Tuchman, as well as a National Jewish Book Award. But its claims were heavily scrutinized by a Princeton PhD student named Norman Finkelstein. Finkelstein, who has since established himself as a vocal critic of Israel, called Peters’ text a ‘monumental’ and ‘threadbare hoax.’ William B. Quandt, a noted scholar of Middle Eastern affairs, said the book was ‘based on shoddy scholarship.’ And Avi Shlaim, one of Israel’s New Historians, called it ‘preposterous and worthless.’

Owing, perhaps, to the intense reaction that her book produced, Peters never wrote or published another word. She passed away in 2015, more than 30 years after the publication of From Time Immemorial, at the age of 78.

Peters’ interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict originated in her work as a freelance reporter during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Israel barely wrestled a victory from the armies of Egypt and Syria. From Time Immemorial was the result of seven years of research, correspondence and writing, as an earnest attempt by an American gentile to understand a conflict that had divided and continues to divide.

But what made it so controversial? Originally intended as an investigation into the plight of the Palestinian Arab refugee, Peters was startled when she found out that “also around 1948, whole Jewish populations from numerous Arab countries had been forced to flee as refugees to Israel and elsewhere in the world.” As the book underwent its gestation, Peters began to doubt the multiple claims made by the Palestinians and various human rights organizations, among them the claim of Palestinian Arab refugee status; that Arabs had lived in Palestine ‘from time immemorial’ only to be displaced by the waves of European Jewish immigration; that Arabs and Jews shared the land in harmony, but the emergence of Zionism created conflict because the Jews wanted a state for themselves.

From her investigation into these claims, as well as her examination of the demographics of Palestine during Ottoman rule and the British Mandate, Peters presented several counter-claims:

that the Palestinian refugee problem was “misrepresented and misunderstood”, and their prolonged refugee status was being exploited by neighboring Arab countries as a political weapon against Israel.

that owing to the comparable number of Jewish people being displaced from Arab countries, what happened between 1947 and 1949 should be considered a “population exchange”, similar to that of India and Pakistan, and Greece and Turkey.

that the Jews of Palestine suffered unbelievable discrimination and second-class citizen status, both under Ottoman rule and the Mandate. Especially under the Mandate period, Jews were the target of hate, restrictions, and attacks enforced by Arabs.

Most controversially, Peters suggested from her demographic investigation that the land of Palestine, under the centuries of Ottoman rule, had barely been settled before the arrival of Zionist Jews. Moreover, it was the result of Jewish cultivation in the 19th century that land became prosperous and attractive to the Arabs. Peters concluded thus:

The land called Palestine was never considered a nation at all, and surely could not have been regarded by the later immigrants as their "ancestral" homeland, any more than a Norwegian immigrant to the United States would consider that his "ancestral" home was the United States when his ancestors were born in Norway.

In other words, if she is right, then Palestinian nationhood is a mere fiction and a pernicious tool of anti-Israel propaganda.

As a supporter of peace between Israelis and Palestinians based on the two-state model, I do not welcome this conclusion. The two-state solution, a target of constant attacks and ridicule, starts on the basis that both peoples have legitimate claims to statehood. The fact that states like Pakistan or Jordan are considered legitimate by virtually all other nations, despite having virtually no national history before their formal independence, shows that statehood is a legal claim rather than a historical one. Ukraine, whose citizens are fighting a courageous battle against the Russian invaders, only declared independence in 1991. Still, as a gesture of respect for its sovereignty, we call it ‘Ukraine’ instead of ‘the Ukraine’. As long as it does not invalidate the claim of Jewish statehood, the legitimacy of Palestinian statehood should be honored and respected.

Secondly, Peters’ downplaying of the Palestinian refugee problem as a mere “population exchange” ignores the legitimate grievances that generations of stateless Palestinians have harbored against Israelis. Yes, we should be aware of the weaponization of this ongoing tragedy by bad-faith actors, but that does not mean we should, in the manner of Pontius Pilate, wash our hands of our responsibilities towards this beleaguered population. As the noted New Historian Benny Morris shows, Arab villages were destroyed and Arab villagers were expelled by the Haganah (the precursor to the IDF) during Israel’s War of Independence.

The bitterness that surrounds the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, from the point of view of this non-Jew and non-Arab writer, stems from the assumption of complete guilt on one side and complete innocence on the other. By dispelling the myths of Arab innocence, Joan Peters’ From Time Immemorial unfortunately affirms the myths of Israeli innocence. Neither narrative serve the cause of peace. To quote the great Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who knew full well the human cost of war:

For decades God has not taken pity on the kindergarteners in the Middle East, or the schoolchildren, or their elders. There has been no pity in the Middle East for generations… Our peoples have chosen us to give them life. Terrible as it is to say, their lives are in our hands. Tonight, their eyes are upon us and their hearts are asking: How is the authority vested in these men and women being used? What will they decide? What kind of morning will we rise to tomorrow? A day of peace? Of war? Of laughter or of tears?