How Herbert Marcuse Predicted Woke Capitalism

And how conservatives can learn from him

The year 1964 found America in an upheaval. The Civil Rights Act was passed. President Lyndon B. Johnson was up for re-election. Republican nominee Barry Goldwater spearheaded the nascent conservative movement. The Gulf of Tonkin incident was used as a pretext for further military intervention in Vietnam. A New Left began to spring up. Exemplified by the radicalism of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), it directed its criticism not just at the current administration’s policies, but at the very American idea of capitalism and freedom.

It was against this backdrop that Herbert Marcuse’s seminal work, One Dimensional Man, was published. Subtitled “Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society”, the book hurls a sledgehammer at the respective ideological frameworks governing Western capitalism and Soviet communism. Its publication earned the author an honorary role of mentor and guru to the new generation of leftists, including the black radical activist (and now tenured professor at UC Berkeley) Angela Y. Davis. Thus, you can barely imagine my surprise when I found out that Marcuse also has followers among the American Right, most notably Paul Gottfried, the editor of the conservative monthly magazine Chronicles. It was after meeting Gottfried for my podcast that I became interested in reading Marcuse. If there is an objective to my recent essays, it is to encourage critical engagement with some of the West’s most important and controversial political thinkers, alive or dead. I hope I can do the same in regards to Marcuse.

If you are tuned in to American conservative discourse today, you may hear the phrase “cultural Marxism” or “neo-Marxism” thrown around with some frequency. Either variant has been used by Jordan Peterson, Christopher Rufo, and James Lindsay, among others. The Israeli conservative philosopher Yoram Hazony even coined the phrase “woke Neo-Marxism” to describe this emerging ideological scourge. It is most likely that these thinkers are referring to the Frankfurt School, of which Herbert Marcuse is a part. The term is in reference to the Institute for Social Research, founded in 1923 in Frankfurt am Main. Aside from Marcuse, the most well-known figures associated with the Institute were Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Gyorgy Lukacs and Jurgen Habermas. Steeped in Kant, Hegel, Freud, Marx, and the Continental tradition of Western thought, these audacious minds set out to understand how authoritarian and totalitarian politics can be reflected in a given culture, borrowing from a multitude of disciplines such as cultural studies, psychology, and sociology. Having been castigated by Nazi Germany and disillusioned by the failed Soviet revolution, these thinkers are amongst our foremost authority on what totalitarianism does to its subjects, especially those who gave it power.

The phrase “critical theory”, in particular its variation “critical race theory”, has been unjustly abused by right-wing pundits - often simplified as representing wanton subversion. To be sure, Marcuse and his Frankfurt counterparts were subversive, but they were far from wanton. One Dimensional Man, perhaps his most subversive text, is as much an attack on advanced industrial society (capitalist and communist) as it is a call for liberation from invisible forces of social control:

Late industrial society has increased rather than reduced the need for parasitical and alienated functions (for the society as a whole, if not for the individual). Advertising, public relations, indoctrination, planned obsolescence are no longer unproductive overhead costs but rather elements of basic production costs. In order to be effective, such pro- duction of socially necessary waste requires continuous rationalization — the relentless utilization of advanced techniques and science.

Marcuse was undoubtedly soured by his experience living as an expatriate in America. Instead of seeing it as a land of liberty and the rightful victor of the War against Nazi Germany, he saw a land of utter decadence, of confusion, of people who traded their freedom for the so-called liberties of the republic. In his seminal treatise Civilization and Its Discontents, Sigmund Freud saw civilization as a means of subjugation of the ego over the id - human’s base desires for love and death subsumed over the need to coexist with one another. If Freud is right, Marcuse believes, then America represents the height of civilization, and thus the height of repression.

This was the thesis of his other well-known work, Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud, published in 1955. Intended as a critical study of Freud, Marcuse applied Freud’s thesis of civilization and subjection to advanced industrial society at large. The popular images associated with middle-class American life - a well-fenced suburban home, a well-paying job in a nearby city, a happy wife and several happy kids, etc. - are all signs of culture exercising its power to subjugate the individual:

The high standard of living in the domain of the great corporations is restrictive in a concrete sociological sense: the goods and services that the individuals buy control their needs and petrify their faculties. In exchange for the commodities that enrich their life, the individuals sell not only their labor but also their free time. The better living is offset by the all-pervasive control over living. People dwell in apartment concentrations- and have private automobiles with which they can no longer escape into a different world. They have huge refrigerators filled with frozen foods. They have dozens of newspapers and magazines that espouse the same ideals. They have innumerable choices, innumerable gadgets which are all of the same sort and keep them occupied and divert their attention from the real issue- which is the awareness that they could both work less and determine their own needs and satisfactions.

It is no surprise that one of the 50s’ most popular films is Rebel Without a Cause, and one of the most popular novels is On The Road. Both present the ideal American life as conformist and repressive, and in both works, the protagonists engage in active rebellion against the life they were brought up in. It should come as no surprise, also, to find some of the New Left’s most prominent voices, such as Mario Savio and Abbie Hoffman, coming from the college-educated background. It is as if they, like Keanu Reeves in The Matrix, swallowed the red pill upon entering the halls of academia, and all their misgivings about modern society are confirmed at once. We see modern-day incarnations of Savio and Hoffman in the student rebellions under the disparate banners of Black Lives Matter, LGBTQIA+ rights, and #FreePalestine, among others. They are not going to be receptive to arguments of the contrary because, Marcuse believes, it is not the cause they are fighting for, it is the society they are fighting against.

This, I believe, is what separates the New Left from the old. While the old left, i.e. the labor movement and acts of civil disobedience, acknowledges the legitimacy of the authority they are petitioning against, the New Left ruthlessly discards that belief. With the help of Critical Theorists like Marcuse, the students of elite schools do their very best to challenge the very society they live in, often without presenting a viable alternative. This is par for the course with thinkers of the Frankfurt School: while rejecting both American capitalism and Soviet communism, neither Marcuse nor Adorno can provide a legitimate model of social organization to replace them. Rebels without a cause, indeed.

So what does all this have to do with Woke Capitalism? Unlike Christopher Rufo, I do not believe that wokeism is a radical movement taking over the institutions via a long march envisioned by Antonio Gramsci. Instead, it is the institutions of media, academia and business that have taken over wokeism, rendering it palatable to the masses. What the numerous tales of journalists and academics being canceled from their respective institutions (Andrew Sullivan from New York Magazine, Bari Weiss from the New York Times, Joshua Katz from Princeton University) obscures is that the majority of their former colleagues have embraced woke politics. Thus, instead of seeing them as heroes who fight against the tide of tribalism, we should see them as outliers discarded by a system in disarray.

After the one-two-punch which are the 2008-09 Economic Recession, and the failure of the Iraq War, institutions no longer command the trust of its people. This erosion becomes worse after the 2016 election of Donald Trump, and the Covid pandemic that erupted in 2020. In his lifetime, Marcuse’s pessimism was going against the tide of optimism experienced by Americans after winning the War and during a period of economic prosperity. If he was living in this day and age, the same pessimism would not be out of place.

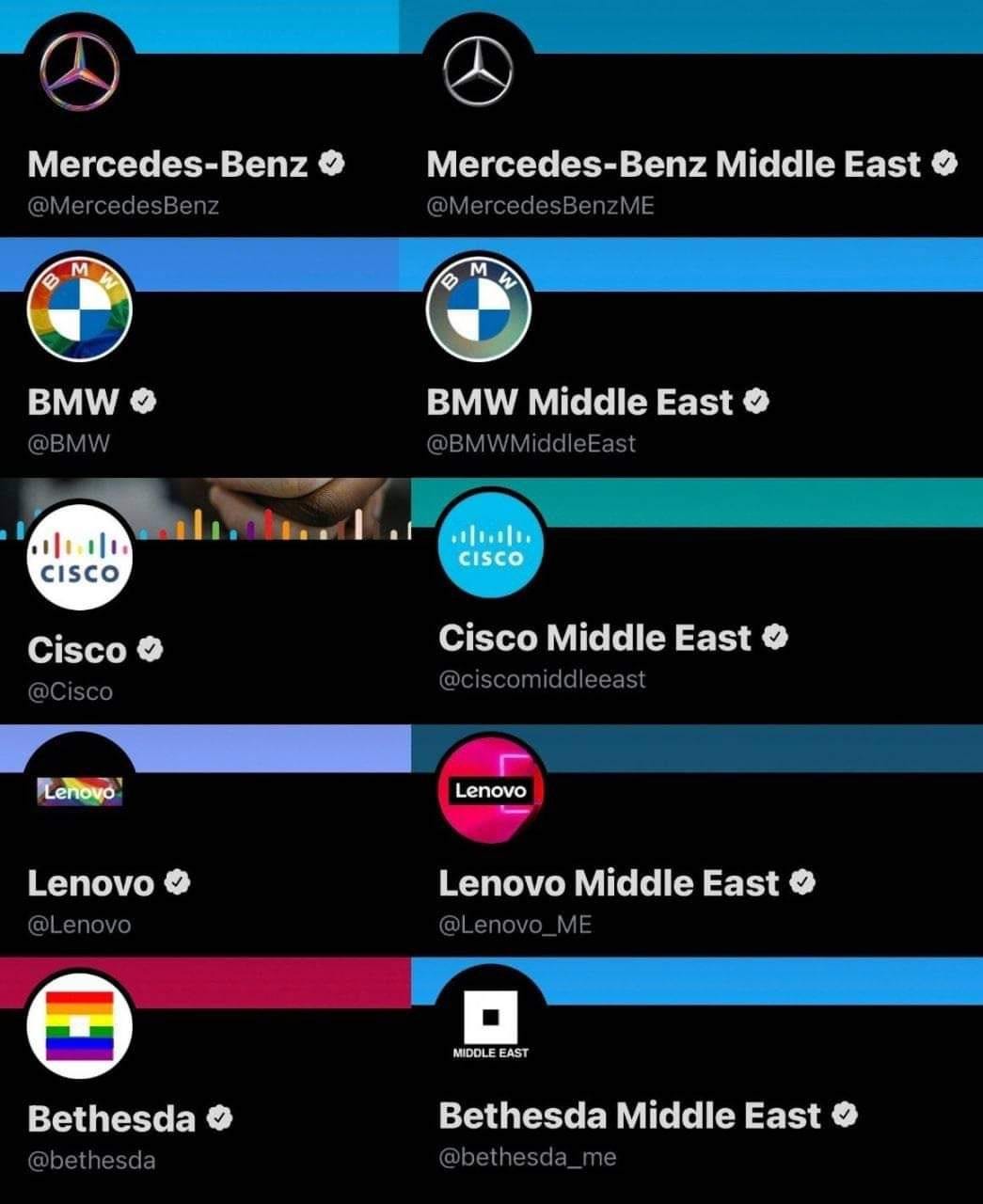

In his upcoming book, How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement, the Marxist writer Fredrik deBoer will show that wokeism, though it may have its roots in the progressive Left, has been successfully co-opted by the very same institutions whose legitimacy is scrutinized. The most egregious manifestation of this phenomenon being Fortune 500 draping themselves in the Pride flag during the month of of June (but not in their Middle Eastern divisions, mind you). Thus, Pride, allegedly started by ‘black trans women’ of Stonewall Inn., becomes just another corporate accessory.

What many prominent voices of the Right such as Chris Rufo and James Lindsay fail to notice is that while they deride Marcuse and the Frankfurt School as the ideological wellspring of woke, they are actually participating in the same methodologies Marcuse used to sow doubts about our society. Rufo’s new book, America's Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything, for example, may put himself in ideological opposition to Marcuse, but both he and Rufo have come to the conclusion that powerful institutions of American life exert control by co-opting cultural movements. Culture, in turn, happily acquiesced.

Conservatives who care about freedom should remember what the philosopher-comic George Carlin said during a taping of Real Time with Bill Maher: “When fascism comes to America, it will not be in brown shirts or jack boots - it will be in Nike sneakers and smiley T-shirts. Germany lost the Second World War, but fascism won.” Marcuse could not agree more. After the near-fatal blow to the American economy in 2008, capitalism needed a human face, and it went with wokeism (again, not in the Middle East, mind you).