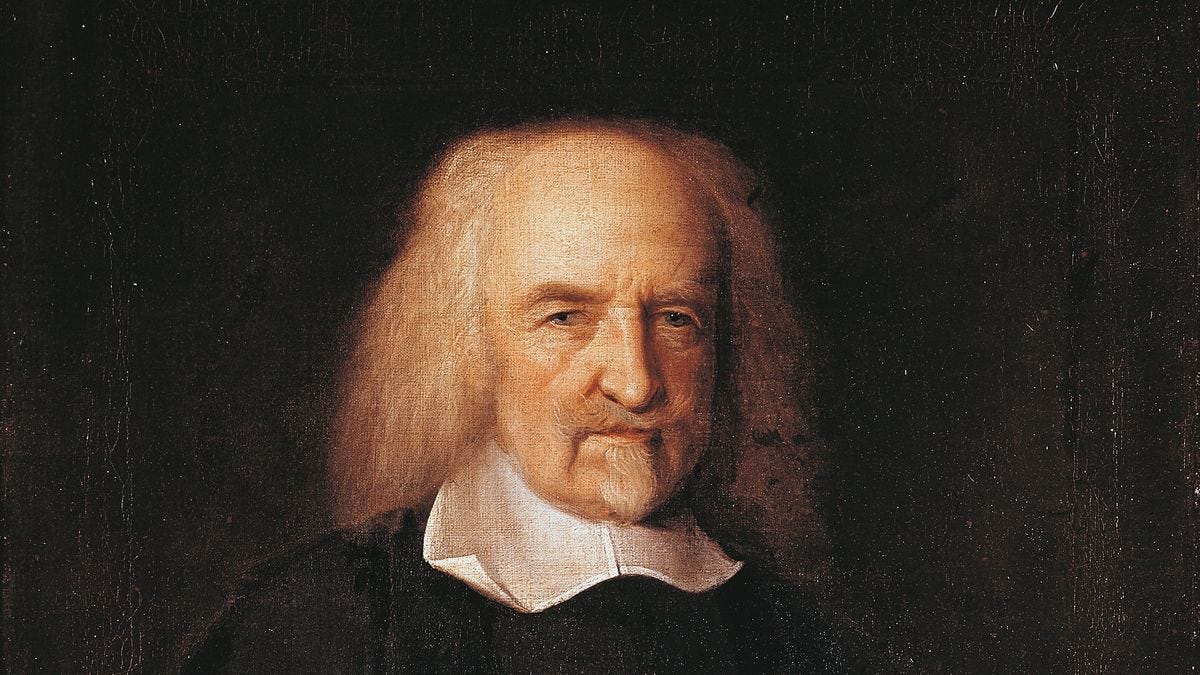

Despite being hailed as one of the the most influential thinkers of modern political thought, Thomas Hobbes never left behind a school of thought bearing his name. While scores of theorists and would-be theorists go by Platonists, Aristotelians, Thomists, Kantians, Nietzscheans, Marxists, and even Heideggerians, “Hobbesian” is mostly associated with the the succession of five attributes Hobbes believes are inherent in pre-government human existence: “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Setting aside the fact that life can be all those things even with the existence of government (as the people living under the North Korean regime can attest), Hobbes’s idea of the “state of nature” have become the standard starting point in any political science class.

A state of war, “of all against all”, is how Hobbes envisions our lives before the emergence of political order. Although anthropologists and historians may quarrel with this conception, such a state can manifest itself in the absence of effective government. Such is the state in Iraq immediately after the fall of Saddam, Libya after Gaddafi, Somalia since the 1990s, and New York City during a blackout. In such a state, would the ordered tyranny of North Korea and Iran be preferable? In his best known work, Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, Hobbes states clearly his pessimistic view of human nature:

“Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of war, where every man is enemy to every man, the same consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them withal. In such condition there is no place for industry... no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death.

What is less well-known is that in Leviathan, Hobbes undertook a radical departure from traditional political philosophy. In his 91 years of life, Hobbes witnessed a series of upheavals that fundamentally changed his home country of Britain. There was the English Civil War, which divided the island nation between Royalists and Republicans; the execution of Charles I, which thoroughly destroyed the notion of divine right of kings; the short-lived Protectorate period, marked by the brutal reign of Oliver Cromwell; the return of Charles II and the Restoration of the English Crown. Furthermore, Francis Bacon’s advancement of the Scientific Method and René Descartes’s radical case for Skepticism raised doubts about the legitimacy of traditional ways of thinking. Thus, the most important text of modern political thought, and the most cohesive justification of tyranny, can be seen as an attempt to free humanity from anarchy.

Hobbes rejects Aristotle’s view that “man is by nature a political animal”. Aristotelian-inspired scholastic theologians such as John Duns Scotus and Peter Lombard are deemed “two of the most egregious blockheads in the world.” Instead, he embraces another figure of Ancient Greece: Thucydides. Having translated the great general’s account of the Peloponnesian War into English, Hobbes wishes also to translate Thucydides’ insights on war and civilization into modern-era Britain. Even though it is not a work of political theory, Thucydides intended for his historical account to be a part of every statesman, political philosopher, and military commander’s library: “My work is not a piece of writing designed to meet the taste of an immediate public, but was done to last for ever.” Perhaps Hobbes’ greatest inspiration from Thucydides came from the general’s vivid descriptions of the failings of Greek democracy. For every great leader such as Pericles, there is a succession of demagogues like Cleon and Alcibiades. And when democratic Athens fell to oligarchic Sparta, Athenian democracy fell also, replaced by the oligarchy of the Thirty Tyrants. For Hobbes, democracy is inherently unstable, for it can lead to such demagoguery and tyranny. Additionally, he has no patience for the Virtuous Leaders and Philosopher Kings envisioned by Aristotle and Plato.

Leviathan, therefore, is not a guide to statesmanship, but what entails a leader’s legitimacy. Dubbed “the sovereign”, this leader does not rule by divine mandate, but from the consent of his people. This form of sovereignty is legitimized by a “social contract.” More implied than written, it is a pact signed by the entire citizenry to confer absolute, unquestionable power to one of its members. This one individual, the sovereign, can be anybody, regardless of one’s social status, level of income or wealth, gender or ethnicity. This is where modernity begins: with the people, rather than God, deciding who to rule. The sovereign, thus, is no less than an unchallenged tyrant. Under his rule, the people have virtually no rights save for the minimum necessary for self-preservation. Dissent is unthinkable, since rebellion means violating the social contract. Additionally, because the sovereign is granted power by his people, any form of dissent means going against the people as a whole. Being an absolute ruler, the sovereign wields the power of the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary, as well as both spiritual and temporal power. Hobbes would find the idea of separation of powers, advocated by John Locke and Montesquieu after him, utterly absurd, since it defeats the notion of an all-powerful monarch. Under this sovereignty, the individual citizen is entitled to no more than the protection of his life. A good statesman, in Hobbes’ view, can be found in Kim Jong-Un and Ayatollah Khamenei.

But how did Hobbes’ successors, Locke and Montesquieu among them, find in him the seeds of individual freedom and limited government? For one, Hobbes make a forceful, albeit pessimistic, argument in favor of human equality. In the state of nature, all humans are equal in strength and intelligence, and thus each individual poses a contrast threat to his fellow man:

If nature therefore have made men equal, that equality is to be acknowledged: or if nature have made men unequal, yet because men that think themselves equal will not enter into conditions of peace, but upon equal terms, such equality must be admitted. And therefore for the ninth law of nature, I put this: that every man acknowledge another for his equal by nature.

It is hard to believe that the argument for human equality, which inspires every national liberation movement from the American Founders to Gandhi, has such a pessimistic and radical origin. What Hobbes is proposing is no less than a delegitimization of preconceived social hierarchies, divinely inspired or otherwise. No matter one’s class, race, gender and creed, we are all motivated by self-interest, and are fearful of our fellow man’s potential harm against us. Even the mighty Achilles, says Hobbes, could be killed by less powerful hands when he falls asleep. This is where Hobbes depart from Thucydides’ grim view that “The strong do what they can; and the weak suffer what they must”: in the state of nature, the distinction between the weak and strong is irrelevant, for everyone poses the same level of threat to everyone else.

Hobbes’ contribution to liberal thought also comes from his powerful assertion that it is the people who decide their ruler, independent from divine will or foreign imposition. Any committed believer of national self-determination would tell you that it is preferable to be ruled by a member of his own nation, even if he turns out to be a dictator, than to suffer the reign of a foreign agent, even if he is a democrat. This is the idea which animates right-wing opposition to the European Union found in the UK and Hungary, as well as the left-wing opposition to American hegemony in Latin America. It also animates the Ukrainians’ fight against Russian domination, and the various movements of stateless peoples calling for their rightful place in the globe, from the Uyghurs to the Palestinians and beyond. Hobbes cleverly shifted the central question of political philosophy from “Who should rule?” to “Who decides who should rule?” For it is not yet decided who or what should govern global affairs, in the realm of international relations, we remain in the Hobbesian state of nature. But within functional states, a government is considered legitimate even if its people do not possess fundamental rights, for it has accomplished Hobbes’ minimal requirements for a good statesman: to hold absolute power over the citizenry, and to lift the populace from the state of war of all against all.

Finally, Hobbes’ social contract proposes a radical vision of inclusivity, for it automatically assumes that every individual will be a signatory to the pact. From the long history of Western countries excluding women from the political process to the rejection of “untouchables” from Hindu public life, all forms of political organization have a feature of exclusivity. Even in the ancient democracy of Athens, women and slaves were not allowed in the deliberation process. For Hobbes, all people are participants of the social contract, explicitly or otherwise. We are currently living in an age of expanding liberalism, what Jürgen Habermas calls the unfinished project of the Enlightenment. This means that a liberal public square cannot sustain itself without the participation of all its members, or at least the explicit assumption that all members are welcome to participate. Thus, to paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr., illiberalism anywhere is considered a threat to liberalism everywhere. The Russo-Ukraine war, for example, currently serves as a test case for the legitimacy of national self-determination, as well as the equality of sovereign nations in the international sphere.

It is not easy to characterize Hobbes using contemporary political labels. He can be either a proto-liberal, a conservative, a reactionary, or all of these at once. Nevertheless, within political philosophy seminars, his reception is a mix of respect and derision. On one hand, professors and students focus on his view of the state of nature and the social contract. On the other, his idea of an all-powerful Leviathan is automatically seen as tyrannical. With notable exceptions such as Carl Schmitt, this seems to be the established treatment of Thomas Hobbes. I dissent from this treatment, for it aims to sanitize Hobbes for liberalism’s consumption. Hobbes is a powerful thinker precisely because of how illiberal he is - the insights which inspired his liberal successors are only the by-product of his advocacy for a bottom-up tyranny. Instead, what we should pay closer attention to is the question of whether tyranny is a better alternative to anarchy, and the state of nature as a fierce rebuttal to the doctrine of Natural Law. Looking through this lens, Thomas Hobbes comes across as both authoritarian and radical, something that is anathema to our modern sensibilities.