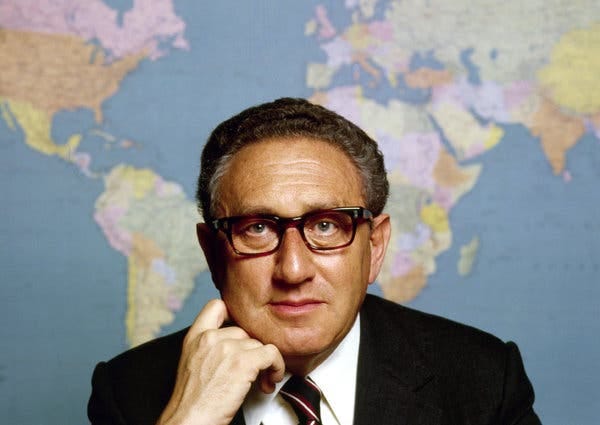

The truth is: I have never bought into the line of thinking that tries to accuse Henry Kissinger of being a ‘war criminal’. And from my experience, most Vietnamese who are concerned with international affairs do not think so either. Either it is because he helped end America’s involvement in Vietnam, or simply because he was a master international relations strategist. For me, reading Niall Ferguson’s biography of Kissinger was my entry point into thinking about foreign affairs seriously. And to his credit, Ferguson made Kissinger admirable and human. Here was a Bavarian Jew narrowly escaping the Nazi murder machine, only to come back to his country of origin to join the de-Nazification efforts. Here was an immigrant who fulfilled the criteria of the American Dream and beyond - Harvard Professor, Secretary of State, doyen of American foreign policy officials. Here was a man who, through direct involvement in the Vietnam War, realized the folly of excessive idealism and the need for sober-minded compromise.

Kissinger was a conservative in every sense of the term. The late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan once quipped: “I was forty before I had any real idea what Burke was about; Kissinger knew in his cradle.” This does not mean Kissinger did not find himself at odds with the American conservative movement. His decision to open American diplomatic relations with China, as well as his détente with the Soviet Union, prompted William F. Buckley Jr. and the right to “suspended their support for Nixon’s reelection.” Kissinger’s legacy also proved vexing to the American Jews, who often cite his opposition to Moynihan’s stance against the United Nations during the Zionism-is-racism crisis (“We are conducting foreign policy. … This is not a synagogue”), as well as his perceived Machiavellian strategy during the 1973 Israeli-Arab War (“[the] best result would be if Israel came out a little ahead but got bloodied in the process”). But his refusal to conduct international affairs in terms of moral and political ideals is the essence of his conservatism. For this reason, in an America where rhetoric of moral exceptionalism prevails, Kissinger’s political philosophy was never given the proper welcome.

But it is his philosophy that America should consider as it is facing domestic and international decline. We are now in the Election Year of 2024, where two of the least popular Presidents - Donald Trump and Joe Biden - will vie for re-election. The columnist Douglas Murray puts it best when he say: “If Biden does win, America will be headed for four years of serious decline on the world stage… But if Trump wins, I seriously expect America to burn.” Internationally, China is mere inches away from Great Power status, an aggressive Russia is devastating its neighbor, an Israel traumatized and “bloodied” by Palestinian terrorists, and a rest-of-the-world that no longer believes in an American-led global order. “Decline is a choice,” said the late Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer, and America has chosen it. Having been in power during the 1970s, Henry Kissinger knew all too well what America’s decline looks like - a rising China, an unwinnable situation in Vietnam, an Israel traumatized and “bloodied” by hostile Arabian forces. Perhaps, Kissinger thought, one way to reverse decline is to learn how to accommodate it, at least in the short-term future.

It is no coincidence that Kissinger’s final book published in his lifetime is a study of political leadership, for the West is lacking a good deal of it today. Currently, it is a non-Western leader whom the West looks to as a role model for political statesmanship - Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Zelenskyy’s inspirational heroism in the face of Russian invasion and war warrants careful studying, but his war with Russia has to come to an end before that can happen. “[I]f the allies succeed in helping the Ukrainians in driving the Russians out of the territory they have conquered in this war,” said Kissinger in an interview with Andrew Roberts. “they will have to decide how long the war should be prolonged.” In other words, while it is Zelenskyy’s leadership that keep the war effort going for as long as it takes, it is the responsibility of the West to put the war to a stop. At this stage - nearly two years since the Russian invasion - the outcome of war has to be decided not on the battlefield, but the negotiating table. This is not unlike the end of the American phase in Vietnam, where Kissinger himself negotiated with both the North and South in 1973 to ensure effective American withdrawal. Russia in 2024, like America in ‘73, has to be compelled to negotiate, and the West has to apply pressure on Putin to do so. “For the first time in recent history,” Kissinger suggests. “Russia would have to face a need for coexistence with Europe as an entity, rather than America being the chief element in defending Europe with its nuclear forces.”

The great dilemma of statesmanship, for Kissinger, is to “strike a balance between values and interests and, occasionally, between peace and justice.” There is no doubt that a negotiated solution to the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, like the 1973 Vietnam negotiations or a hypothetical future peace deal between the Israelis and the Palestinians, will be perceived by some to be unjust. Thus the tragedy of statesmanship, as Kissinger learned in his tenure in government, is Hegelian and not Greek - the stateman's choice is not between good and evil, but two or more comparable goods. A declining America has to understand that its resources are limited, and so is it influence on the world. The Reaganite slogan “We win, they lose”, inspiring as it may be, should be reserved for a more prosperous and triumphant time. For now, it is better to practice humility, so as to avoid humiliation.

Requiescat in Pace to Henry Alfred Kissinger (1923 - 2023). May your lessons be learned and your legacy be debated for decades to come.

Now write one about Hitler! Tell us about a declining Nazi Germany, how Europe looked up to Mussolini as a model leader, and the tragedy of statesmanship in the Holocaust.

You write elequently, but you're not fully in touch with reality, making the fancy structures you build ring hollow when knockedbagainst a few hard realities.