The Anti-Slavery Project America Forgot

On the American Colonization Society & the Founding of Liberia

As we look forward to the newly-created American federal holiday of Juneteenth, let us look back at a chapter in the anti-slavery movement which has been overlooked in the present ‘legacy of slavery’ debate. Before abolition became the stated aim of the movement, there was an initiative to transport all the emancipated slaves and free blacks of America back to the African continent. Despite founded on philanthropic intentions - to encourage the black population to strike out on their own - it was tainted with racist assumptions of black Americans’ inability to integrate into the American mainstream. And it did nothing to ameliorate the intense debate on the ‘peculiar institution’ that would culminate in the Civil War.

That initiative was the American Colonialization Society. It was founded in 1816 by Robert Finley, a Presbyterian clergyman and educator. According to Columbia historian Eric Foner, until around 1830, colonialization - “the removal of the black population from the United States” - was the rubric under which most antislavery activism took place, at least among white Americans: “Absurd as the idea of colonialization may appear in retrospect, it seemed quite realistic to its advocates.” On one hand, Finley and the Society believed that the black man is entitled to a life free of bondage and racism. On the other, the ACS feared that free blacks will encourage slave to revolt against their masters. Gabriel’s Rebellion, a planned slave revolt in 1800, forced the Founders to directly confront “the chasm between the ideal of liberty and their messy accommodations to slavery.”

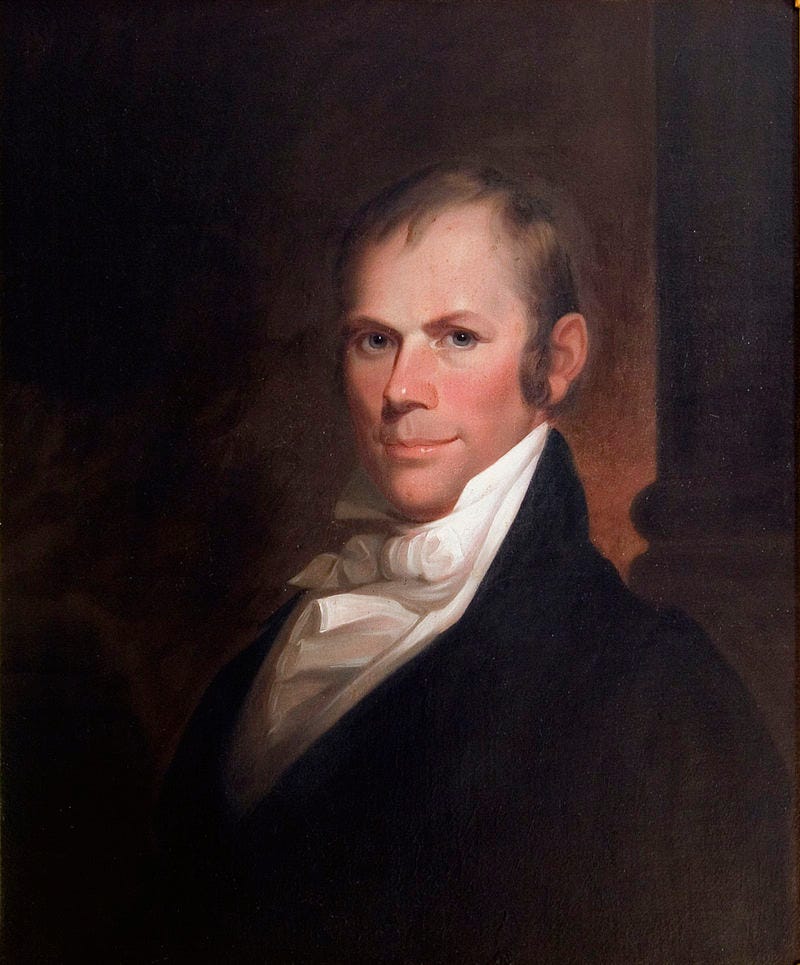

The ACS was notable for its popularity in the American South - it branches were mostly set up in the Southern States. Its presidents tend to be Southerners and slaveholders. Among them were Bushrod Washington, nephew of George and a Supreme Court Justice, and Henry Clay, the great Senator from Kentucky. Since most of the subjects of repatriation were free blacks, Southern slaveholders saw the Society as an expedient opportunity to delay emancipation and increase the value of their own slaves: “Every attempt by the South to aid the Colonization Society, to send free colored people to Africa, enhances the value of the slave left on the soil.”

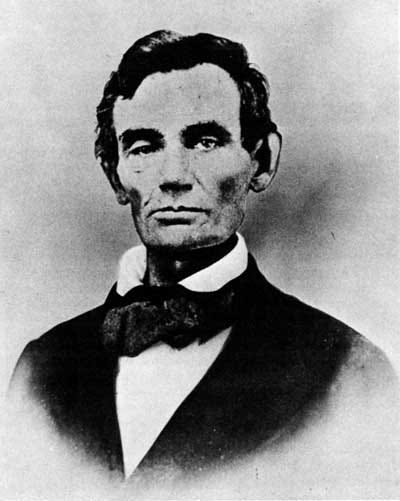

Abraham Lincoln, who viewed Clay as a political role model, was an enthusiastic supporter of colonialization in his early political life. According to Foner: “He found it impossible to imagine the United States as a biracial society. When he spoke of returning blacks to Africa, their ‘own native land’, Lincoln revealed that he did not consider them an intrinsic part of American society.” But after January 1st, 1863, he “made no further public statements about colonization, perhaps realizing that such statements had failed both to persuade blacks to emigrate or to reconcile his critics in the northern and border states to emancipation.”

Lincoln’s change of heart on the slavery question was reflective of a nation-wide turn away from colonialization, and towards abolitionism. By the late 1850s, the ACS was called an “old fogy affair”. And its mission had not been a success either: in 1859, the Society sent around 300 persons to the African colony of Liberia, out of a population “of well over four million.” William Lloyd Garrison, the great abolitionist, was himself a convert from the colonization cause. In his 1832 treatise Thoughts on African Colonialization, he recalled his conversion as prompted by his day-to-day interactions with the black communities across America:

African colonization is directly and irreconcileably opposed to the wishes of our colored population as a body. Their desires ought to be tenderly regarded. In all my intercourse with them in various towns and cities, I have never seen one of their number who was friendly to this scheme—and I have not been backward in canvassing their opinions on this subject. They are as unanimously opposed to a removal to Africa, as the Cherokees from the council-fires and graves of their fathers.

Along with Garrison, several other white converts to the abolitionist cause began to denounce the ACS for “intensifying racial prejudice in America.” Among them was Lewis Tappan, who wrote in an 1835 letter to Henry Clay proclaiming the Society’s ineffectiveness: “Colonialization has not, nor will it… diminish slavery. What is to be done? I answer, emancipate.”

The success of the abolitionist movement was attributed not only to the ineffectiveness and racial prejudice in the colonization project, but also to their profound amendment to the meaning of personal liberty, political community and American citizenship. Lydia Maria Child, in her 1833 treatise An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans, the “Americanness” of the slave and the free black was emphasized over his alleged “African” origin. It must follow that the black man is a fellow citizen, not a foreigner:

I am aware that some of the Colonizationists make large professions on this subject; but nevertheless we are constantly told by this Society, that people of color must be removed, not only because they are in our way, but because they must always be in a state of degradation here—that they never can have all the rights and privileges of citizens—and all this is because the prejudice is so great… This is shaking hands with iniquity, and covering sin with a silver veil. Our prejudice against the blacks is founded in sheer pride; and it originates in the circumstance that people of their color only, are universally allowed to be slaves. We made slavery, and slavery makes the prejudice. No christian, who questions his own conscience, can justify himself in indulging the feeling. The removal of this prejudice is not a matter of opinion—it is a matter of duty.

The legacy of the abolition movement is enshrined in the 13th Amendment, passed and proclaimed in 1865: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” But the legacy of the American Colonization Society lives on also. The West African colony of Liberia became the new home to some 15,000 free blacks between 1822 and the American Civil War. This population would adopt an Americo-Liberian identity, and proclaimed an independent republic in 1847. Tensions soon arose between the Americo-Liberian settlers and the indigenous African population, culminating in decades of brutal civil war between 1980 and the 2000s. Honesty towards the historical record and the legacy of American slavery requires a discussion of the ACS, and its enduring footprint in the African continent.

And what about Marcus Garvey and the Black Star Liner company? He and it are celebrated in Jamaica (at least in reggae music culture) to this day....