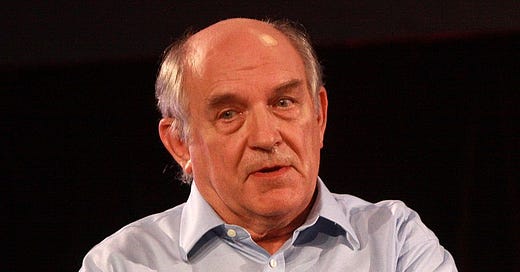

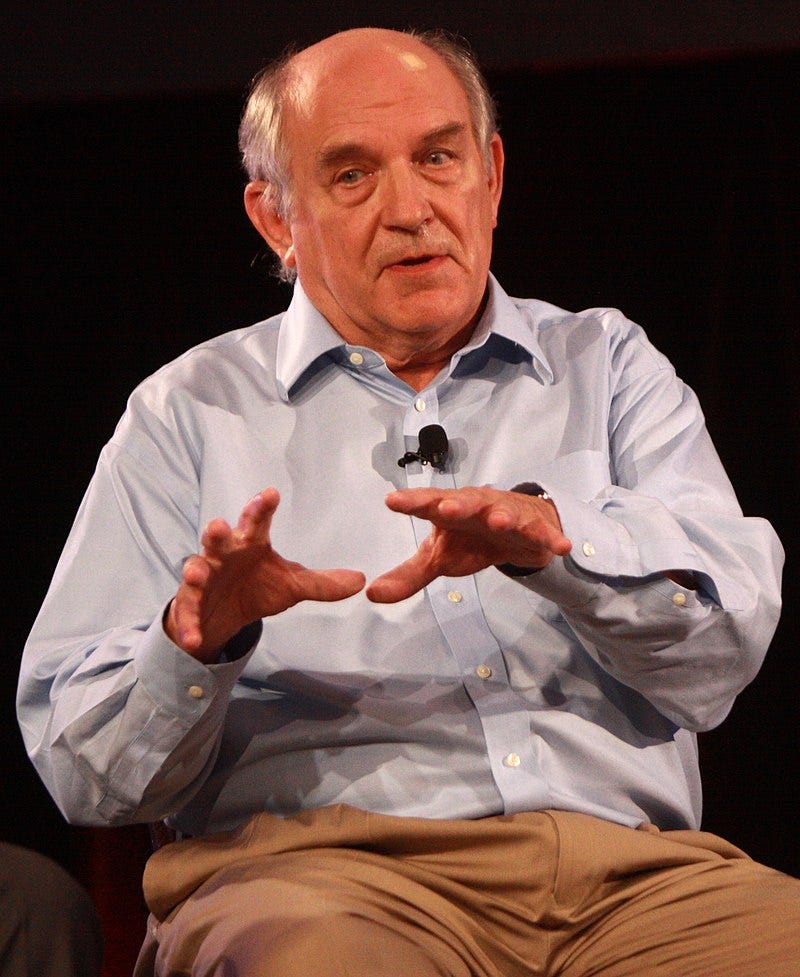

Allow me to begin by this provocative proclamation: Charles Alan Murray, scholar-in-residence of the American Enterprise Institute, is one of the most profound and important living political thinkers in America. Among those who would find that statement disagreeable would be the once-venerated Southern Poverty Law Center. The agency that contributed to the bankruptcy of the Ku Klux Klan has seen it fit to label Murray as an ‘extremist’, claiming that his research uses ‘racist pseudoscience and misleading statistics to argue that social inequality is caused by the genetic inferiority of the black and Latino communities, women and the poor.’ These, and other allegations of Murray’s racial prejudice, stem from the publication of a 1994 book he co-authored. Its full title is The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life.

The book’s other co-author is Richard Julius Herrnstein, a noted psychologist at Harvard University. But because of his untimely passing - which was before the book saw publication - Murray endured the brunt of the backlash. The question of intelligence in relations to race is addressed in two of the book’s chapters - “Ethnic Differences in Cognitive Ability” (Chapter 13), and “Ethnic Inequalities in Relation to IQ” (Chapter 14). Controversial as the contents of these chapters are, they should not distract us from the book’s central thesis. Throughout the pages of ‘The Bell Curve’, Herrnstein and Murray presents a tectonic shift in the class stratification of American society, which enormously favors the cognitively well-endowed at the cost of everyone else. Cognitive intelligence, they argue, is the key element to success and mobility in the changing, globalized world. Through meticulous and staggering data analysis, the two authors show the gradual formation of a wealthy and influential ‘cognitive elite’, as well as the overwhelming disadvantages faced by those with below-average or average IQ scores. ‘[T]he twenty-first [century],’ writes Herrnstein and Murray. ‘will open on a world in which cognitive ability is the decisive dividing force… The isolation of the brightest from the rest of society is already extreme; the forces driving it are growing stronger rather than weaker.’

This book-length wake-up call has unfortunately been drowned out, partly by the controversy surrounding the book’s two chapters on race, and partly by the triumphant ‘Unipolar Moment’ that America experienced after becoming the sole-remaining superpower in the 1990s. Murray, for his part, has revisited the topic of cognitive stratification some two decades later with his 2012 book Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010. But the growing populist backlash against ‘the elites’, best represented by Donald Trump but was born out of Obama-era grassroot movements from both the Left and Right (Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party, respectively), forces us to re-examine the social divide that we have accepted as given since the end of the Cold War. The professional class, which I consider myself a part of, must reckon with the enormous advantage they have accrued for themselves while taking seriously the legitimate grievances voiced by those less fortunate than them. Thirty years on, ‘The Bell Curve’ remains a hard pill to swallow, but if we wish American democracy to be healthy again, swallow it we must.

Trump is only the latest manifestation of the American antipathy towards intellectuals. He does not talk like someone with a fancy Ivy League degree, and he does not care whether or not you have one. What he represents is a growing skepticism of the political capital that such a degree brings to its bearer. It is not inherently wrong to be a Harvard or Yale graduate, but a government populated by Ivy League alumni risks being aloof and contemptuous to the values held by the governed, while pursuing ambitious but lofty domestic and foreign goals which threatens the stability of the polis. As the Notre Dame political theorist Patrick Deneen writes: ‘A political and social order led by the progressive ethos of expertise will inevitably reinforce transformative conditions that require more expertise… [I[n a progressive society, the default “ignorance” of the masses becomes the rule and the norm.’

This callousness of the new cognitive elite also results in what Charles Murray calls their unwillingness to ‘preach what they practice’. As shown in 'The Bell Curve', even though high-IQ people marry and have children much later in life, they have a less likelihood of getting divorced. Only 9 percent of those classified as intellectually ‘Very Bright’ get divorced within the first five years of marriage, and only 2 percent of women classified as such give birth to illegitimate children. Meanwhile, among the bottom quartile of IQ scores, the percentage of households with children that have experienced divorce and that of those with children born out of wedlock are 33 and 23 percent, respectively.

But nowadays we hear our wealthy ‘elites’ seriously considering polyamorous relationships, disguising it as ‘ethical non-monogamy’. In another example, the University of Chicago philosopher Agnes Callard divorced her colleague and husband of eight years to pursue a relationship with one of her graduate students. It was the stuff of your average Woody Allen comedy, but Callard saw it fit to use her personal life as a teaching moment. According to her profile in the New Yorker, eight years after their divorce, Callard and her former husband ‘held a session called “The Philosophy of Divorce”, which was attended by hundreds of students.’ My friend Rod Dreher - also a divorcée - puts it best when he says: ‘It seems to this reader that Agnes is being a self-centered hooch, but dressing it up as some kind of philosophical virtue… It's all like a chapter in Paul Johnson's great book Intellectuals, which is about how monstrous some great thinkers behaved towards people in their private lives.”

It turns out that the cognitively gifted also suffers from the most human of vices, intellectual hubris and moral blindness. Instead of denigrating the poor, as he was accused by the SPLC, Charles Murray sees them as those who got the short end of the stick in a society where intelligence, not moral virtue, is rewarded above all else.