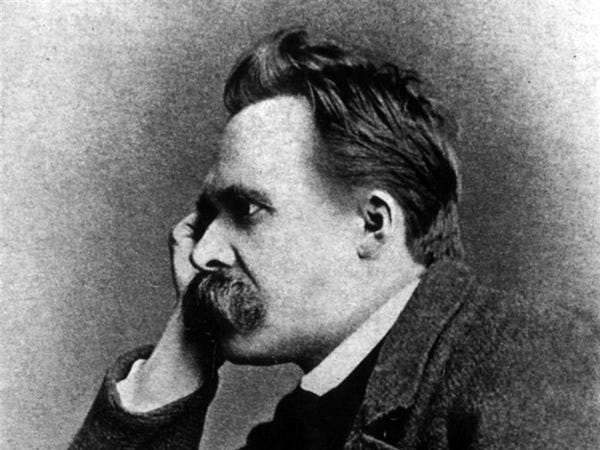

My first introduction to Nietzsche was through the actor Paul Dano, specifically his character in the 2006 sleeper hit Little Miss Sunshine. In the film, Dano plays an angsty teenager who reads too much of the German, and has taken a vow of silence (which he hilariously breaks at the middle of the movie). I did not know enough philosophy back then, but my mind instantly made the assumption that Friedrich Nietzsche’s premier demographic were (male) teenagers with bottled-up anger and confusion. And I was one of them.

I was entering high school when I first watched the movie. Little Miss Sunshine, as well as countless other titles I found through endless browsing on IMDb.com, provided an escape from the torturous years of adolescence. Although the statement has become a teenage cliché, high school was a living hell for me. I had no friends, school was tough, I had no idea which college to apply for, I did not know what I wanted to be after I finished high school. I only wanted for it to be over.

That set the stage for my first exposure to Nietzsche’s ideas: encountering the two phrases “God Is Dead” and “the Übermensch”. Almost instantly, I gravitated towards these two concepts, despite having only the faintest idea of their significance. From the former, I reinforced my budding anti-religious convictions: the God that is worshiped by everyone the world over is a fraud who causes misery among His creation, including myself. And from the latter, I developed a heightened sense of self from my sore outcast state: the only reason why they don’t accept me into their social environment is because they are mediocrities who feared excellence, and I vow to show them how wrong they are by being the best at what I am good at. I harkened back to the parable of the river crabs: if one of them gets captured and put in a bucket, he can escape through the power of his endurance and willpower. But if a lot of them were caught and thrown in the same bucket, they will never get out, for the ones who try to escape are held back by the vast majority. I am going to spare you the long story of how I came to repudiate Friedrich Nietzsche’s poisonous philosophy, but I can reveal to you that it started with me finally reading him.

“All the sciences have now to pave the way for the future task of the philosopher; this task being understood to mean, that he must solve the problem of value, that he has to fix the hierarchy of values, ” Nietzsche writes in ‘The Genealogy of Morals’, his audacious critique of Christian ethics. I find it to be the most revolting work of moral philosophy I have ever read. This is not because I have since become a Catholic - I still enjoy reading the works of New Atheist thinkers like Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens - but because of Nietzsche’s fanatical glorification of the Will to Power and his seething contempt for the weak. This is why I cannot be all too aggrieved when I learned of his midlife descent into mental invalidity and dependence upon his sister’s care - in a twist of ironic fate, he becomes the weaklings he thinks so little of. Every page, every letter in this short work is seething with contempt for what he deems ‘slave morality’:

“They are miserable, there is no doubt about it, all these whisperers and counterfeiters in the corners, although they try to get warm by crouching close to each other, but they tell me that their misery is a favour and distinction given to them by God, just as one beats the dogs one likes best. That perhaps this misery is also a preparation, a probation, a training; that perhaps it is still more something which will one day be compensated and paid back with a tremendous interest in gold, nay in happiness. This they call ‘Blessedness.’”

“It is not surprising that the lambs should bear a grudge against the great birds of prey, but that is no reason for blaming the great birds of prey for taking the little lambs.” Here he evokes the same line of argument made by Thucydides, followed by Machiavelli and kept alive by the contemporary Ukraine-skeptical ‘realists’: The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must. The problem, Nietzsche believes, arises when the weak devise a morality of their own, wherein acts are not treated as ‘good’ and ‘bad’, but ‘good’ and ‘evil’: “And when the lambs say among themselves, ‘Those birds of prey are evil, and he who is as far removed from being a bird of prey, who is rather its opposite, a lamb, — is he not good?’” It is not surprising, therefore, to know that Nietzsche once revered the Nordic pagan gods, known for their superhuman feats of strength and apathy for humankind.

In contrast, the Christian God is a symbol of self-sacrifice and mercy, a repudiation of the pagan idol-worship of strength. Nietzsche, whose father was a Lutheran pastor, saw Christian faith as nothing but a long con, perpetuated by the priesthood to wage war against the mighty: “What wonder, if the suppressed and stealthily simmering passions of revenge and hatred exploit for their own advantage their belief, and indeed hold no belief with a more steadfast enthusiasm than this— ‘that the strong has the option of being weak, and the bird of prey of being a lamb.’” Whereas the Enlightenment-based critique of Christianity employed by Hitchens and Harris maintains respect for the cornerstone liberal value of religious tolerance, Nietzsche saw Christianity as intolerable, contemptible, and to be repudiated with extreme prejudice.

Nietzsche is equally unsparing to the Enlightenment. As Allan Bloom writes in ‘The Closing of the American Mind’, modern democracy “was…the target of Nietzsche's criticism. Its rationalism and its egalitarianism are the contrary of creativity. Its daily life is for him the civilized re-animalization of man. Nobody really believes in anything anymore, and everyone spends his life in frenzied work and frenzied play so as not to face the fact, not to look into the abyss.” This line of criticism has enjoyed a revival through the works of contemporary post-liberal thinkers, most notably Patrick Deneen’s controversial monograph Why Liberalism Failed: “The sole object and justification of this indifference to human ends—of the emphasis on ‘Right’ over ‘Good’ — is the embrace of the liberal human as self-fashioning expressive individual. This aspiration requires that no truly hard choices be made. There are only different lifestyle options.” If Marx’s theory of alienation is used to attack Enlightenment liberalism from the political Left, the Right launches its attacks using Nietzsche’s concept of the Last Man. The political scientist Francis Fukuyama, in his groundbreaking text The End of History and The Last Man, brilliantly appropriated Nietzsche as a foil to his Hegelian proclamation of history’s final destination:

“The typical citizen of a liberal democracy was a ‘last man’ who, schooled by the founders of modern liberalism, gave up prideful belief in his or her own superior worth in favor of comfortable self-preservation. Liberal democracy produced ‘men without chests,’ composed of desire and reason but lacking thymos, clever at finding new ways to satisfy a host of petty wants through the calculation of long-term self-interest.”

It is not surprising, therefore, to see committed religious thinkers - Deneen being a notable example - borrowing from a figure so contemptuous of their beliefs. The contemporary revival of integralism among prominent Catholics, who believe that the Church should have a hand in the moral guidance of civil society, shares Nietzsche’s concern about liberalism’s propensity to deny absolute truth. The philosopher Yoram Hazony, writing from a Judaic and nationalist perspective, argues that liberalism is as much a universal political theory as Marxism, and thus is inherently neglectful of culture-specific moral values: “To understand politics, we must think in terms of causes such as nation and tribe, mutual loyalty, honor, hierarchy, cohesion and dissolution, influence, tradition, and constraint.” In other words, thymos.

Hazony blames the rise of illiberal political trends, such as wokeism on the Left and populism on the Right, as directly caused by Enlightenment liberalism. This is not unlike Nietzsche’s position that the Enlightenment is the dagger that killed God, and the Will to Power is the resulting moral landscape we inherit: “Where has God gone? I shall tell you. We have killed him – you and I. We are his murderers. But how have we done this? How were we able to drink up the seas? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What did we do when we unchained the earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now?” In other words, if we have the power to murder God, nothing is beyond our capability and will.

Hazony, as well as his post-liberal counterparts, is wrong to believe that liberalism gives birth to anti-liberal politics. It is not unlike believing that atheism is caused by Christianity. But this is the logical conclusion when one adopts Friedrich Nietzsche’s moral philosophy, which states that truth is no more than the reward coveted by multiple ideologies and interests vying for political and social power. Of all Nietzsche’s acolytes, Michel Foucault stands among the most successful in adapting his thoughts to the 21st century. You cannot view the current debate around “gender identity” without the lens of Foucault’s politics of biopower, most enthusiastically adopted by the gender studies philosopher Judith Butler in her quest to redefine “man” and “woman”.

What is “wokeism” if not the use and abuse of the victim status? Unfortunately, as the Right begins to take up the rightful cause of fighting this mutation of left-wing progressivism, conservatives have been infected by the “woke” virus as well. For example, the conservative Rod Dreher argues, in his bestselling book The Benedict Option, that the truly marginalized population in America are orthodox Christians. Christopher Rufo, who used to be a sophisticated critic of ‘Critical Race Theory’ and radical gender ideology, has made boogeymen out of both concepts while allying with Florida Governor Ron DeSantis to wield state power against dissenting ideas. Donald Trump succeeded in crafting a personality cult around him - which now includes one major American political party and even formerly respectable conservative think tanks - precisely because he has hoodwinked a large portion of Americans into believing that they are being victimized by mass immigration, free trade, and the ‘elites’. Even if he never holds political office again, the cultural Grand Canyon that he has wrought shall take decades to heal, if it heals at all.

As the woke Left and populist Right engage in political and cultural trench warfare, liberalism is suffering its worst blows. Friedrich Nietzsche, who in his life waged a similar war against the virtues of Christianity and liberalism, is now reaping the spoils. As the conservative thinker Arthur Brooks has warned in this book Love Your Enemies, we have entered a politics of contempt, and it takes the same values that Nietzsche thinks so little of - decency, compassion, and forgiveness - to wrestle a way out.

Thank you for your response! Personally I do not believe that Christian morality leads men towards bitterness and nihilism. And judging by the final years of Nietzsche’s life, he seemed to have fallen into the same abyss he warned his readers about.

You may have read Nietzsche but you didn’t read him closely. Here’s a friendly rebuttal of the first part of what you wrote.

First, let me just say at the outset that Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens are intellectual midgets compared to Nietzsche, to say nothing of the fact that they are comparable to the antisemites of Nietzsche’s time, read “Islamophobes” today. Islamophobia is the new antisemitism, or didn’t you know? Nietzsche would have despised Harris and Hitchens for their selective outrage and he made fun of “atheists” whenever he could. That much should be clear to anyone who has read Nietzsche closely.

The main reason why you get Nietzsche wrong is because you’re overly focused on weakness. What Nietzsche opposes in GM is resentment, not weakness. What he is against is the family of reactive feelings that invented Christian morality and what he seethes against is the fact that this morality has been sold to Western civilization as morality itself, as if no other morality had any standing or credibility.

The real target of his hatred in GM is not the weak but the priests. The priests are not even weak. They are resentful and full of concealed hatred. The priests are able eventually to subdue even the masters and to get them to subscribe to their new subversive morality which allows them to become masters. His real target is Christian morality, not weakness.

Also, Nietzsche does not have “apathy for humankind.” His entire philosophical corpus is intended to save mankind from the snares of a diseased way of thinking and to offer man a way out of nihilistic despair and a life lived in bitterness and regret.

I’ll leave it there for now.