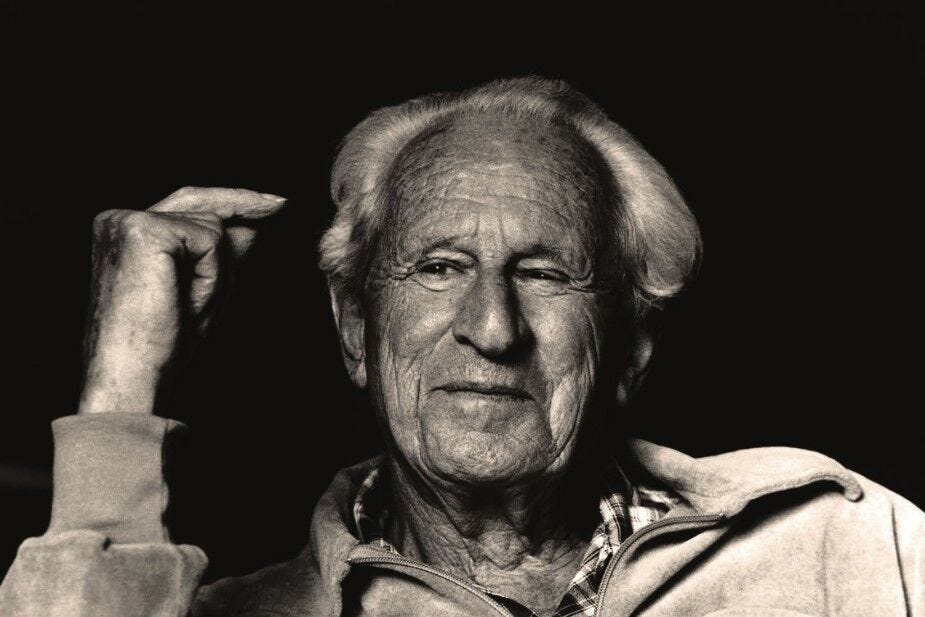

In the preface to his short book The Spirit of Liberalism, the conservative philosopher Harvey Mansfield identifies himself as “a friend of liberalism” and the book to have been “written in defense of liberalism”. At the time of the book’s publication (1978), Mansfield saw liberalism’s enemies not only in the New Left, but “even more by the failure of liberals to defend themselves.” These days, as the forces of illiberalism sort themselves in both the political Left and Right, liberalism finds itself fighting on two fronts - the ‘Woke’ Progressives on one flank, and the ‘Common Good’ Conservatives on the other. Given that these two groups have been claiming more politically-minded young people in their memberships, it is not altogether inappropriate to draw inspiration from the wisdom of our elders.

True conservatism, after all, finds a balance between Progressivism’s reckless motion forward, and the misty nostalgia of post-liberal National Conservatism. Mansfield is among the few to strikes this balance with consistency. Having spent seven decades in the halls of Harvard University, both as a student and a faculty member, he observes with impeccable clarity liberalism at its best, as well as its greatest errors. “To defend liberalism,” Mansfield states. “liberals must be critical of the enemies they tolerate and speak up against them. The true liberal speaks up; he does not speak out.” This means tolerating an illiberal, even anti-liberal viewpoint, without falling into the temptation of moral relativism. Radicalism, according to Mansfield, becomes liberals’ greatest weakness, for it possesses “both the whole and the partisanship that liberalism needs” while relentlessly calling out liberals for their inconsistencies. The phrase “repressive tolerance”, popularized by the Frankfurt School theorist Herbert Marcuse, reveal the central liberal dilemma of whether intolerance can be tolerated in an open society.

Marcuse, who was openly hostile to liberalism, nevertheless received warm embrace from the liberal institutions he worked at, in addition to the warm welcome that liberal America extended him. To this end, his status as liberalism’s greatest challenger in America becomes more relevant. As I have pointed out in a previous essay, today’s anti-liberal conservatives treat Marcuse the same way Herod Antipas treated John the Baptist: they denounce him with the utmost fervor in the public square, all the while absorbing his teachings in secret. On the other hand, liberals’ biggest mistake is to treat him as a friend and ally. “Despite their accusations against liberals,” says Mansfield. “radicals [like Marcuse] present themselves as friendly to liberals…not by direct appeal to liberal philosophers and statesmen, but with the apparently liberal doctrine of the liberated self.” This is the reason why Wokeism, despite its withering disdain for the liberal institutions, has become so quickly and easily integrated into the same institutions. While the connection between Woke politics and Marcuse has been widely exaggerated by the likes of Chris Rufo and James Lindsay, there is no question that Marcuse’s doctrine of “repressive tolerance” has made its way into the Woke mindset. How else can you explain the expanding administrative departments specifically designed to enforce ‘diversity, equity and inclusion’?

Liberalism, with its pessimism of human nature and optimism of human reason, strikes a balance between the rights of man and the limitations of man. Liberals, however, find themselves tempted always by the notion of human progress. Martin Luther King Jr.’s invocation of the moral arc of the universe bending towards justice may be compelling, but it is far from historical fact. Like Dr. King, liberals believe not only in the inevitable march towards progress, but they believe also that this progress is inevitable. Even the conservative slogan “Standing Athwart History, Yelling Stop” admits of inevitable historical progress. In instituting the New Deal, Franklin Delano Roosevelt - the quintessential American liberal - was not only attempting to resolve the financial crisis brought about by the Great Depression; he was also implementing a program he thought would advance economic justice to all Americans. It is this unwavering belief in progress that blinds liberals towards their enemies, often those on the Left.

But today, a new attack on liberalism is being waged from the Right. Whether it goes by National Conservatism or Common-Good Conservatism, this emerging force is aiming it spears neither at the current political Left nor Right, but at a “consensus” that both sides appeared to have made regarding the preservation of liberalism. For mainstream American conservatives, liberalism undergirds the core of the nation’s founding. For liberals, liberalism fosters progress for the country’s marginalized groups. This is why (left-)liberals failed to stem the tide of wokeism, with its illiberal and impatient programs of social reform, all the while blaming conservatives for acting defensive. But with the oncoming illberalism of the Right, perhaps a pro-liberal left-right coalition can be enlisted. After all, what can be more exhilarating can being a moderate in an age of extremes?

Harvey Mansfield offers a helpful reminder to his liberal friends of two important qualities of liberalism: it is anti-utopian, and it is for the patient:

To make a very realistic beginning has always been the great supposed advantage of liberalism. No one can say that Hobbes’s state of nature is a Garden of Eden, and yet when correctly understood it shows how men can trust one another on a purely human basis without reference to something above or beyond man. It seems to show how we can control ourselves. We do it by consent.

To the liberal, the most alluring temptation is towards a social utopia. To the conservative, the most dangerous vice is reactionary politics. For the liberals, Mansfield reminds them of liberalism’s origins as a revolutionary doctrine. For the conservatives, he reminds them of the virtues necessary to keep liberalism alive, namely prudence and tolerance. Liberalism may have found its mature form in Locke, but it was raised on the cunning virtù Machiavelli and the the absolutist misanthropy of Hobbes. As I have established in a previous essay concerning the latter, it was Hobbes who introduced a radical conception of legitimacy as coming from below, not above. At its core, liberalism is the answer to the vexing question of how a society can contain a multitude of ideas and beliefs. Thus, liberalism well understood seeks not to rule, but to preserve peace and legitimacy. In contrast, according to Mansfield:

“[C]ommon-good conservatives want to rule. They see or sense that the common good is associated with rule, while liberalism, in its 17th-century sense, depends on representation — a diversity or alternation of power that is something less than rule. They therefore attack not only the liberals of our time, but also the generic liberalism of the 17th century, together with its tradition of modifications and improvements since then. They challenge the very idea of a society of rights in which government represents rather than rules the people.”

Of all the values cherished by liberalism, tolerance seems to have courted substantive ire amongst the New Right. In a recent essay for City Journal, the famed activist Christopher Rufo calls for broad state action against the twin ideas of Critical Race Theory and Critical Gender Theory, citing Richard Nixon as an example:

As president, Nixon ruthlessly dismantled the radical organizations, such as the Black Panther Party, Black Liberation Army, Weather Underground, and Communist Party USA, that threatened violent revolution against the state. His FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, launched a sophisticated campaign to infiltrate, disrupt, and disperse their networks, with devastatingly effective results. Of course, some of what Hoover’s FBI did ran the gamut from questionable to flatly illegal, and these practices not only violated the rights of numerous American citizens but also undermined the authority by which the U.S. government rightly engages in containment of lawless individuals or groups. Still, by the end of Nixon’s first term, most of the subversive organizations had imploded, and many of their leaders were on the run, in prison, or in the ground.

Similarly, the Presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy calls wokeism “a cultural cancer that threatened to kill the American dream.” It would seems that today’s so-called conservatives covet not the cool-headed optimism of Ronald Reagan, but the conspiratorial pessimism of Nixon. Ramaswamy himself heaps praise for Tricky Dick in an article for The American Conservative: “As U.S. president, I will respect and revive Nixon’s legacy by rejecting the bloodthirsty blather of the useful idiots who preach a no-win war in Ukraine that forces our two great power foes ever closer.” While both Rufo and Ramaswamy are correct in announcing today’s politics as a re-run of 1968, the last thing we need is a Republican Right that matches the Left’s level of radicalism. Instead, we need to re-embrace the radical conception of inalienable rights and constitutional government brought forth by our liberal forebears.

As the generation of conservative defenders of liberalism are replaced by an intellectually vibrant but politically hot-headed New Right, Harvey Mansfield’s counsel carries more weight than ever. To understand what liberalism is, Mansfield believes, we must know what liberalism is not: utopian, elitist, anti-tradition, etc. Liberalism does not strive for a perfect politic, but a decent one.